She has come after an absence of many years. The cab was late, she is angry and her neck hurts, up the back, over the top of her head, so that she tries to remember not to rub it as she sits on her chair in a row with others. She doesn’t want to be angry at the cab driver, doesn’t want to worry that her headaches could mean a tumor or cancer. Doesn’t want to be afraid of aging and death, always afraid and worrying. She knows it isn’t just age. When she was young she was also a believer and she rode through her life feeling held from behind and below as if in a rickshaw, calm and still as she moved without fear into her future. She knows that her faith gave her those things, cheerfulness, generosity, detachment, faith strong enough to cast out fear. But she can’t find her way back.

It is Good Friday afternoon, the Passion has been reenacted by the school children and the church is dark, quiet and cool. The statues have been draped in purple all of Lent, and now, in addition, a further stripping away, the flowers have also been removed from the altar and the three layers of white linen reverently folded by the young altar servers, so that the altar is bare, just wood, which she finds almost embarrassing in its nakedness.

She had forgotten that people see each other in line, see each other come out of the confessional, some crying, some not, some inside a long time, others briefly. Waiting is both public and deeply private. Two teenage boys stand, letting older men and women like herself have their chairs. The first boy goes in, comes out, moves silently to a pew and kneels, lost in his thoughts. She moves a chair closer. In the half-darkness a simple candle casts a warm light on the confessional’s narrow door.

On the floor, at an angle against the shallow steps that lead to the altar, a wood cross larger than life rests and on it the corpus. One by one, people kneel down, touch it in their different ways, a hand lingering, another stroking, an embrace, a kiss. One woman shows her young child, a baby girl just learning to walk, to be quiet and still, to wait.

It is hard to keep awake, her body folded over on the chair, hard because it is all more beautiful than she remembers and the beauty weighs down on her like a heavy cape. Hard because the strangers are welcoming in their reserve, hard because she feels all that she has missed, time folded over and onto itself like a paper bird with pert wings, those sharp folds of something flat into something that could fly, the Holy Spirit like a dove, all of it pressing down with awe and sorrow, sorrow being time’s twin.

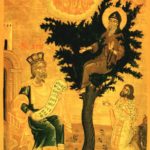

After an absence of more than thirty years, she’s at last come back inside the walls, into the body of the whale, and it is more beautiful because it is more real to her than she expected, that is the trouble, and that is why she is staying, why she has taken the little hand-made book out of her purse and fingers its rough edges while her eyes are closed, feels the tiny white stitches where she sewed the center seam, the uneven bulkiness because on some pages she also taped images cut from magazines, art museum catalogues, photocopies from art books in her home because the images spoke to her of what she had written in various inks over the years, blue, black, green, making a Bible of her own, a testament where she could cast a thread through the silence and separation and anger of those years, some line to catch herself, strong enough to bear her full weight, dragging her through the water, the hook still caught in the side of her cheek, the cheek flesh healed around it, the wounds of Christ, lying, as he is now, on the incline of the shallow steps leading to the altar, his long carved legs bent at the knee, the nail driven through the arches of his feet, one stacked on the other like kindling, that ancient way of seeing him, timeless, that ancient way of saying, “Suffering is why I came, Bernadette.”

Maybe she will show the priest her book. See where my needle carried the thread? See this picture of Adam I taped in? See this image of Mary Magdalen, so sorrowful with her jar of oil?

Her little book with its tidy Table of Contents. She has come because she somehow wants to join the book to the corpus on the floor, the faithful moving slowly up the aisle to reverence it, the wood and paint and real people, real pews, real altar, that place of radical change, real nails that were hammered into real flesh centuries ago, all of it, ancient and visceral, weaving and interweaving of past and present, waking and dream, to make of all of it, if that joining is possible, one thing, one glorious, true thing.

Eyes still closed, she feels the cool pages for the image of Adam, the first. To the artist, it wasn’t Adam, but to her it became the image of the one she calls, “the Maker.”

Slumping on her chair, the line long, she dreams each story again as if it were new.

Grimoire spell book stock by moxylyn is licensed under CC BY 2.0 / cropped from original