“Tell me about them,” Isaac said when Sarah revealed that he was not the first child born but was the first to survive and took him to the place marked off by a fence where flowers grew inside it and out.

She drew back in memory to that room always at her fingertips where the details glittered, unmistakable, and said, “Nathan was an archer, and your father made him a small bow and five arrows. The bow was red and the arrows had quail feathers. Deborah loved to sing, so I let her nap outside, under the tree. Zachary was taken from my breast. I’d wrapped him in a blue blanket that morning when your father took him from me. He was our first. The blanket is buried there,” she pointed. And Isaac wept with his mother.

Many days Isaac and Sarah walked to the field of flowers and many times he asked her about his brothers and sister, to hear again the details, which she gave to him unaltered, day after day, the exactness of the repetition holding him like a protecting veil.

He learned from her that love sees the other and pays attention to what it sees and he wanted to be like Sarah. Of the flowers that grew by the fence, he asked, “What are these?” “Carnations,” she answered. “See how their petals are variegated, being both red and white?” And he did see. “And these?” “Butterflies,” she said.

“Tell me about myself,” Isaac finally asked because he could not see himself clearly either. Much of the time he didn’t feel visible at all.

He studied her carefully as she spoke, memorizing her words because they felt like news to him and they were news.

“Well,” she began, “your knees are a bit bony but your arms are very strong.” He looked down at his body. “You cry out in your sleep and you have every night since you came down from the mountain.” He returned to her eyes, binding himself to them. “When you were young, you liked spiders and frogs,” she smiled.

They waited a long time. Then he asked, “Am I here?”

“Of course you are here, Isaac. You’re right here with me.” She reached out both hands and touched the sides of his face. “These are your two ears,” she said. “And these, your two eyes.” She laid her hands on his lashes, then continued to his ankles and feet. “You are Isaac, my son. My beloved.”

Many days they went to the field and Isaac asked her to do the same thing, never tiring of being seen and being touched by her at the same time. “You have two ears, two eyes. You are here, Isaac,” she said. “Feel the sun on the backs of your hands? Feel it warming the top of your head?” And he tried to learn it.

When she died, he grieved for her in the field where he lay in great stillness, studying the red and the white of the carnations, the rough wood of the fence, the flight of the butterflies and told himself, “I am Isaac. I am here. And I am real.”

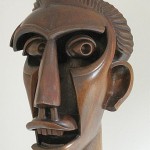

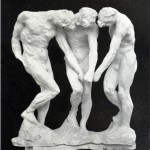

One day as he slept, he saw a fountain glistening in the sun, and on it, three youths. Their heads were bent down, their arms crossed over their chests and he recognized them as his brothers and sister even though they all looked exactly the same. He remembered when he lay strapped firm to the stones that his father looked down but didn’t really see him there. His eyes were glazed and intent, as if seeing something with a painful clarity that Isaac was not part of, something more real than Isaac and the stones and the wood, the fire and the blade.

Isaac meditated on the fountain and wondered if this was how his father saw each of his brothers and his sister when they, too, were on the mountain. That they lay under a film through which their father saw only the innocence he desperately wanted. And Isaac wondered if in those moments, knife in the air, they each had disappeared from his view as he had disappeared. That they were each only a passageway for their father. And he considered, then, that sometimes violence is not even personal, which was another wounding. And he saw, given its power to blind, that the hunger for innocence in an adult can be the most dangerous hunger.

Auguste Rodin, The three shades (Les Trois Ombres), for the top of The Gates of Hell, before 1886, plaster. See page for author [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons