Joseph saw the followers of his son increase rapidly and dreamt that they would continue to increase until time came to an end. He saw that experience would be put into words and heard a creed that was starting to form, followers calling Jesus, “God from God, Light from Light, begotten not made, one in being the Father.”

He lay in his room, just his donkey outside in the courtyard, the arbor with its dormant vine. It seemed he was dying, but he wasn’t quite sure. Though he still didn’t want them, dreams came, and he remembered his cousins saying when he was young, “Here comes the dreamer!”

Sliding in and out of sleep, he saw a future in which some men and women would be reverenced after their deaths like his son already was, and some would be given patronages. He, too, would become such a patron, attached to the well-being of cabinetmakers, carpenters, confectioners, dying people, and engineers. But he would also be the patron saint “against doubt,” which saddened him.

Some would believe that he and Mary never married but remained betrothed only. Some, that he was old when they met, she a child and he a mere guardian. For many, that they had never had sex, much less enjoyed and then missed it, a castrating thought. Worst, to a few, he would be seen as a willing cuckold, letting others devotedly love his wife more intimately than he had and this hurt the most.

It was all awkward like so much else had been. Stepping off a cliff into the still, dark night.

“No one will quote me,” he told himself when the mood came most heavily, seeing again that everything rolled out toward another glory.

And it was true. He would nowhere be quoted in the scriptures Christians collected and formalized, and would not be the object of any special devotion for more than one thousand years.

Outside, the finches and hollyhocks.

Moving in and out of visions and dreams, he saw an ornate city with a central square guarded by a quadragga of life-sized gilded bronze horses. Orphans and unwanted babies were placed in baskets and left there in the portico of a hospital run by nuns who fed, clothed and educated them as they grew. The girls were taught music, the boys trades and the hospital treated people with syphilis and other incurable diseases, the church being named the Incurabili. Joseph liked that odd combination of syphilis, orphans and polyphonic music. That there was compassion where there was little hope. He liked that the church was modest and well-made.

He thought of the Slain Infants, that night that still cut like a ravine, and saw that the church of his son was built on pain that was ancient, unchanging, and inescapable. He recalled that Mary told him she was feeling this when Jesus was just an infant and he regretted having dismissed her at the time, because she was right.

The older he became, the less he understood. The old drawings of the bull tacked to the wall, those years when he hoped to understand his life by simplifying it, were ragged and yellow with age.

He wondered if any of the brothers or sisters of those who were slain became followers of his son. He wondered if any of the Incurabili orphans did. How would faith be possible for them? He had no answer. A breeze through the window, another drawing fell to the floor, and he realized he was an expert in doubt after all.

What he did know, however, he would tell anyone who asked. He would say that there is loneliness in doubting because doubt misses its twin, which is wonder. And there is loneliness in skepticism because it misses its twin, which is awe.

The Angelus sounded in the clay bell down the street.

“Come, my good Master,” the donkey said. “I am taking you to glory.”

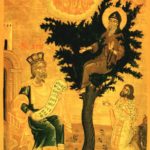

By Mistr Vyšebrodského oltáře (1345-1350), Master of the Hohenfurth Altarpiece (1345-1350) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Cropped from original.