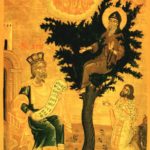

I don’t know why I decided to put what was a separate chapter, titled “Cain in his Garden” back into “Cain and the Dream of the City” as part of that chapter. I wish, now, I hadn’t, partly because I love this image.

Taking this and the other Bible stories on face value, as if they are true, which is my pleasure, I was wondering about Cain late in life, long after he killed Abel his brother, after he was exiled and cursed, after he ventured to the Land of Nod.

When one has experienced real, bloody violence, as Cain surely had in killing Abel, there is great calm in the inanimate world. In The Memory Room the fictional protagonist Barbara stands in front of her therapist, as if at a podium, and delivers a lecture she titled, “What Every Buried Child Knows.” She speaks about the dirt. She has learned, through violence, that the inanimate world— stone, water, dirt–can become a house of refuge.

I thought, Cain came to know the same thing.

There would have been respite in the sound of gravel passing through the tines of a rake. Comfort in the sun heating up the fibers of his clothing, passing through, more gently now, to touch his skin. Satisfaction in making something outside himself, something inanimate that would not cry out, “Cain, look what you’ve done?!” In this way he would fight back. By creating outside himself beauty and order where it otherwise could not be found.

I remembered that when I began to take seriously landscape design, I learned that working in a garden was considered crucial to healing of the mentally ill in the 19th century. Friends Hospital in Philadelphia, for example, opened in 1813 and still going strong, was founded as “The Asylum for Persons Deprived of the use of Their Reason” by the Society of Friends (Quakers). And in their history we see that they early purchased additional land for a hospital garden with this exact healing in mind.

The image also reminded me how the idea of the monastic life, particularly the cloistered monastic life, attracted me to Catholicism. It was the 70’s. I read a lot of Merton. Of his many books, I pulled from the shelf the small one, titled Day of a Stranger. In it he writes, “The monastic life as a whole is a hot medium. Communities are devoted to high definition projects: ‘making it all clear!’ The clearer it gets the clearer it has to be made. The more branches you cut back the more branches grow.”

By contrast, he describes the hermit life which he eventually came to embrace, in this way: “The hermit life is cool…It is a life of low definition in which there is little to decide, in which there are few transactions or none, in which there are no packages to be delivered. In which I do not bundle up packages and deliver them to myself.”

I pictured Cain in Merton’s hermitage in Gethsemane, Kentucky in 1965. Perhaps he would live in silence. Perhaps he would die without ever coming to understand what he had done. Perhaps he would lead this kind of “cool” life.

“What I do is live,” Merton writes. “How I pray is breathe….Up here in the woods is seen the New Testament: that is to say, the wind comes through the trees and you breathe it.”

And I thought, for Cain, how there are some things that are better than understanding. And maybe, from his silence and his raking, this better thing would come.

- Thomas Merton, Day of a Stranger. Written in 1965. Published by Gibbs M. Smith, Inc. Copyright 1981 Trustees of the Merton Legacy Trust.

- The title for this Art Reflection comes from the line, “How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea?” by Yeats.

- Notes:

Buddhist monk raking gravel by Josh is licensed under CC BY 2.0 / recolored from original