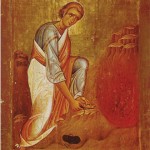

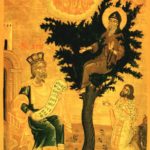

I saw this icon and was struck by its beauty. It is one of the miniature icons that border the large icon of John the Baptist, giving scenes from his life. This one is titled “Elizabeth and the Infant John Seeking Refuge in the Mountain from the Pursuing Soldier.”

It depicts an event in which a mountain opens itself to protect the infant John and his elderly mother during the infanticide ordered by Herod, slaughtering all male children under the age of two. Another bordering icon depicts the “Murder of Zachariah,” John’s father, who was killed in the Temple by Herod’s soldiers because he refused to divulge the whereabouts of his wife and son.

Growing up an Evangelical Protestant, I’d heard of the Slaughter of the Innocents, which is recorded in the Gospel of Matthew, but never of the murder of Zachariah or the story of the mountain. This makes sense because these are not in the Bible. They come from a third century text called either The Gospel of James or The Protoevangelium of James. The “Hiding of Elizabeth” is narrated in chapter 22, the “Murder of Zachariah” in chapter 23 of this ancient text.

The Gospel of James is one of several surviving Infancy Gospels including The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew and the so-called Arabic Infancy Gospel all of which did not make it into the Bible. The early Church judged them to be “apocryphal” meaning of “uncertain authorship” or “secret” and this judgment has been upheld through time by Roman Catholics, Orthodox and Protestant Christians.

Yet, for the Orthodox, the events of the murder of Zachariah and the hiding of Elizabeth and John in the mountain are judged to be true and are revered. This icon is so astonishingly beautiful to me that I began to think more deeply into the relationship between what is beautiful and what is true. And my mind opened to these events. In This is Why I Came I wrote, from this icon of the mountain, what became a series of chapters about John the Baptist, his relationship to Jesus, how their fathers were different, their mothers. And I felt great peace.

Part of the reason I like being a novelist is that I can make true, for myself, things I want to be true. I can re-order actual experience into something else. All the creative people I know make things—a sculpture, a painting, an opera– because they find the world, as it is, to be lacking.

We look everywhere for that thing, even though we can’t name what we are looking for. If lucky, we encounter a piece of it. And we call this “inspiration.” It is a great gift. And, energized, we go on from there, taking the event with us.

I lingered with this icon for many weeks. It was probably something about the notion of a father who would do such a thing, or a mother, elderly but brave, that got me. I’m not sure. Or maybe that the natural world could actually be welcoming, which is not how I usually think of it. In any case I wrote as if these things were true. This child, this father, this mother, this mountain, this danger averted, this heroic death.

For me it didn’t so much matter if the events happened or not. I was very certain of another event that was happening, to me, in the present. The icon, alive in my imagination, was making real what it depicts. Alive in my intellect, alive in my body, alive in the deepest cave of my solitude, the icon was bringing to my hunger, food.

Note: Icon in the border second image from the top right hand side of Icon of John the Baptist.

Icon of John the Baptist by unknown in in the public domain.