Abel, an invalid, in the covering of night, took aim and threw the stone out the window, hitting the ewe. He dragged himself outside, everyone asleep, and thought, this time I will not ask Cain to hide what I have done from our father. Instead Abel slit the ewe’s throat, watched the blood drain onto the grass and slowly, with great difficulty, gathered wood, lit a fire, and waited, hoping, rather than fearing his father, to please him.

In the morning Cain arrived bringing poppy cakes, breads and crackers, flaxseed, cooked squash and onions. He loved his work, setting down the seeds, vines grafted, the grapes better each year, the sweet fruits handled gently, packed in boxes with straw. He’d prepared lentils with mint, parsley and olive oil, his father’s favorite. But when his mother opened the door Cain saw his father already at the table, a bone in his hand, pulling flesh with his teeth, oil dripping from his fingers, the flesh still pink, the fat crispy. “We’ll have those later,” he pointed to Cain’s fruits and grains, waving him in, but Cain stood at the door terrified, then fled.

Blood stained the ground where the young ewe was slain. Weeping, Cain gathered what remained, recognized its soft hide, its four dainty hooves, its head with two ears flush with stiff hair, that it was the new one, the youngest, the one they hadn’t yet named. He wept for the ewe until anger rose up his back like heat and when he stood he knew that he could not not harm his brother. That vengeance would come to Abel, and come through him.

but how its flesh slid between the teeth.

To others Abel was known as the weak brother, tender-hearted, the poor invalid, but to Cain, Abel was the one who threw stones at his sheep, lambs and baby goats, the one who found pleasure that way, wounding them so they could no longer run like the wind but would be broken like he was. Sometimes Abel taunted Cain, taking aim at the first born saying, “He’s like you!” because Cain was the first born, and continued until Cain cried out, “Stop!”

Like fire on dry grass, the news spread and in a short time Abel had assistants, a new livelihood. Animals, no longer given family names, were raised to be slaughtered. Cows, goats, chickens, even the turtledoves. Old words changed their meaning. “Tender” no longer meant an animal’s sweet disposition but how its flesh slid between the teeth. “Tough” no longer fierce and noble like the bull, but a lack of fat and undesirable. Animals became “meat,” their bodies cut into parts and each part also named, “flank steak,” “rump roast,” and “ribs.” Abel taught others how to slaughter mercifully and Cain thought, he’s teaching as if he’d been merciful. My brother a hero. “How did you discover this?” they asked him. “Even my crops are thriving!” “My daughter walks again!” And Cain wondered, is he growing in compassion while I grow in bitterness?

Cain grieved that animals were slain, and always would be slain. He neglected his fields, grapes on his vines withered, then the vines themselves fell. It seemed that blood was everywhere—on tabletops, in bowls, smeared on aprons so that he could no longer bring himself to eat red foods, pomegranate, watermelon, kidney bean. His mother’s consolations fell away like water, making him feel more alone, while his father, jovial and proud of Abel, so long an embarrassment to him, made jokes about the new foods. Eating the calf’s heart, its liver and brains, said, “Surely this is sweet bread!” which stung Cain, his raisin breads and fruit tarts, his barley and dates. “It’s just a joke!” his father said, touching the back of Cain’s head, squeezing his neck for emphasis.

Cain left messages, wanting to be remembered by his family. Nut cakes and fruit spreads in jars tied with string. “Look under the table,” and, “It’s in the garden, love, Cain.” But they did not look. He told himself, I would have looked. I would have read notes from my son.

Everyone seemed to be doing passionate things. A tightrope walker tied his rope between trees and danced across it like a bird. A man lying on the grass held a heavy woman to himself, her thighs like barrels, lost in pleasure, the grass sticking to her legs. A girl in a sleeveless top with shapely arms played a flute for three of her friends. Life had taken a wonderful turn. But when Cain approached a bench to sit down, the women covered their heads with scarves and he thought, they’re pretending to hide their faces from the sun but really they’re hiding from me. A bell tolled two o’clock then three. He watched shoes, the bottoms of legs, sandals, bare feet, ankle bells, toe rings, his eyes most comfortable looking down. A man walked past wearing a skirt flounced out by a petticoat. A print of thrones and, at his sleeves, ruffles. Cain had never seen such a silhouette and it pleased him, but then he thought, I’ve never dressed like that. I have never been original.

He felt inferior to Abel and to anything on which his eye fell. The rabbit is softer than I am to touch. The owl more wise. The raven more bold. The snake more elegant in the moon’s blue light.

In the new world filled with enterprises and projects, memory called to Cain of the life he used to live, held in a cycle of planting and harvest, of bare vines that sprung new leaves and grapes year after year, leaving for a time then re-appearing. Memory called with tiny bells and sweet songs so that Cain tasted it like honey on his lips and tongue, then the back of his tongue, so sweet his teeth ached and, again, his anger grew fierce against his brother.

It was easy. Abel was sleeping when Cain carried him to the spot where the first ewe was slain and, lifting a large stone, threw it down on Abel. And when it was over, Cain felt relief, Abel lying there.

He waited for Abel’s eyes to open, to return like the grape and the wheat, but Abel’s eyes did not open. He watched his brother’s blood seep into the dirt so that the earth became soft like a full sponge and still Abel remained as he lay.

Cain lifted Abel and ran with him to the fields that once were his and made a bed of the dry vines and lay down cradling his brother saying, “You will rise up like the wheat that comes and is gone and then comes again.” But Abel did not rise up. Cain watched Abel’s skin turn blue then white then grey and stroked the cold flesh of his brother as it stiffened. Then horrified, thought, what have I done?

Day after day, Cain lay with his brother on the vine heap, covering him with his body, fighting off vultures, flies, but Abel did not stir. And Cain wept for his brother because he saw that Abel was not like the wheat and the grape and the barley but was like the ewe after all. And he repented for what he had done and wept and wondered, will this come to everyone? And Cain named what had happened to Abel, “Death.”

But on the seventh day, through the dry stalks, through the stiff, putrid body of his brother, came a voice like the voice of the earth saying, “Come, find me, Cain! Come find me!” and it was Abel when they were young, playing in the tall rows of corn, before the accident, when Abel could run like the cheetah. Abel’s voice was alive and real and Cain thought, my brother is neither like the wheat that comes back nor the ewe that is slain. And he considered Abel and thought, perhaps we are all like this, neither wheat nor ewe. And Cain called Abel and himself and his family and neighbors, “Human.”

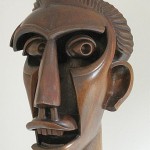

Kopf in Mahagoni, 1921 by Dexedrina is licensed under CC BY 2.0