Five years passed and Jesus was seven. Mary set the table and Joseph planned games. She’d made a cake fashioning animals of almond paste for the top, sheep, camels, rabbits, one for each guest, eighteen in all. She felt that they were help mates again, she and Joseph doing the party together. But no children came. Not the older boys, not any of the girls, except, finally, one, the Gentile girl who came with her cat, but seeing the large cake and none of her friends, set down her present and left.

The plates around the table, the favors and party hats, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus held hands. Looking at his wife to make a point, that she not forget it, Joseph said, “We are a holy family.” She lit the candles and, seeing her husband through them, that he was a person of discernment, a provider of sound judgment, she wondered, is it true? Are we a holy family after all?

As she cut the cake she could almost feel again that surprise when the angel addressed her as an innocent. How at one point he’d looked right into her eyes and she’d looked right into his and consented to what she did not understand because everything he was saying felt both real and good.

Joseph said those words but did not believe them. I, too, have eaten ashes like bread. He thought of his father’s favorite psalm, 137, “They who carried us away required myth of us,” and he tried to do this. Then, “If I make my bed in Hell, thou art there.” He’d memorized all one hundred and fifty psalms by the time he was his son’s age, his father punctuating speech with a psalm day and night, phrases for every mood, happy, dejected, fatigued, energetic.

But he was stretching, to be a holding net, to keep the family together in a claim of innocence that none of them felt. Not Mary, not himself, not their son who’d grown up with the anniversaries, the torchlight processions, the weeping, portraits drawn on the walls in chalk. Families had moved away, many decided they would bring no more children into the world, others divorced, siblings developed strange illnesses. Most no longer observed the Sabbath. “We’ve sacrificed enough,” the boy read on their faces scarred with grief.

Joseph looked at his son and wife and hid his thoughts because, again, he was calculating. The logic came to him often. If he hadn’t been a dreamer, if he hadn’t obeyed the voice in his dreams, if he hadn’t married Mary, she would have been dead seven years now, a thought he despised, as well as their son. But all the other boys would still be alive. Hundreds of them. And Zachariah, too. He said, “We are a holy family,” because he said it to himself often, when the calculating came like a fiendish animal circling the bedpost, the front door, his work bench, and he was ashamed.

When he prayed, which was rare, it was to tell God, in case he’d forgotten, “Send me no more of your dreams.”

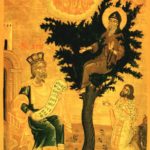

By Ronald (Inge Worringen, Cologne) [CC BY-SA 1.0], via Wikimedia Commons