Sometimes he still feels revulsion toward himself like he did in the days of Nineveh. At worst, it comes like an affliction that staggers him, washing over with such force that he has to hold on to the wall or the arm of a chair to steady himself, sometimes the arm of a stranger. “I am a man with an ice cream cone!” he said out loud just yesterday. “I am just a man with an ice cream cone!” But it slayed him nonetheless.

When it passed and he’d finished his ice cream and almost felt calm again, though exhausted, he remembered the mariners who, despite their distress and terror, did not want to cast him into the sea, but rowed valiantly trying to reach shore. He wanted to be like them then and wants to be like them now. Their smooth, blue features, their clear vision and simple hats.

It was a relief when God let him go and Jonah stepped out of his diamond suit. His wife and child, both happy to have him back, loved him so ardently that on some days he actually felt worthy of their love, felt almost like those sailors, even though they had their gods and he no longer had his. Sometimes he would tell his wife, “I really am a sailor!” and dance with her around the room. He feels it even when his affliction comes, now, two thousand years later, and feels it this afternoon as he sits in a room hearing confessions offered by the faithful.

The second teenage boy has left the confessional and wakes a woman asleep on her chair. When she stands, he holds the door slightly open for her, which surprises her, so kind and unexpected. She begins in an uncustomary way.

“You might have to help me do this,” she clears her throat. “I don’t remember all of the words. It’s been more than thirty years since my last confession.”

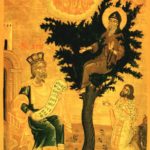

Inside, in the dark pocket, they see each other through the screen. She lowers herself to the worn wood kneeler and sees that what was once three compartments is now all one small room with a narrow passage by which she could step around the screen and speak to the priest directly. To do that, she would have to stoop slightly and walk a few steps to where he sits quietly on a very low stool, vested and still. She feels his deep regard for her, startling in its sweetness, so that she stays composed but only with effort. The dark wood lit by a short candle on a table next to his stool. Like being in the body of a great fish, she thinks, the church its sea and beyond that, the vast sea.

She didn’t expect to cry when she volunteers that she has been all these years in an argument with God because he let things happen that never should have happened.

“I want to believe that he loves the world. And I want to believe,” here she suddenly can’t continue, which she also did not expect, as she’d rehearsed this in the cab hoping to be concise, which is not her strong suit. She wipes her cheeks, which are wet now, because she has come to the center of things. “I want to believe that he loves even me.”

Sometimes the side of his face is to the screen, his eyes closed, his hand holding his chin, and sometimes he turns and looks directly at her and she looks at him. The stool is so low that when they do look at each other, even though she is kneeling, he is still below her slightly so that he looks up to her, which feels intentional and respectful, that he is perhaps there in the service of one thing, which is mercy.

She could live here, she decides, for the rest of her life. Close to everything important, but hidden. She hears the heartbeat in the fleshy walls.

He waits until she has finished and finds he empathizes with the woman on the other side of the screen.

“I don’t feel I’m committing a sin that I can’t believe in God anymore. I can’t will it. What happened, happened. But I really wish it would change. This is why I came.” She wants her integrity and her faith, both at the same time, and Jonah smiles, the breathing of the whale, the constant flow of water around his face and body, water in and out through the baleen, seaweed tangled in his hair. He wonders if, on one day at one hour, she yelled the same thing at God, “Let me go! I’m no longer your prophet! I want to be a sailor.”

“It’s not a sin to refuse to believe in a God who’s too small,” he replies and his certainty touches her. “To doubt the God you believe in is to serve him. It’s an offering. It’s your gift.”

She knows people are waiting on the cool, hard chairs but she does not want to leave.

“Are you sorry for your sins?” he asks with a clean directness that brings her back to the matter at hand. She sees sorrow is what now matters to him and she remembers that it is part of the formulary. That he has to ask her this, the hinge on which the sacrament rests. She is sorry for her fear and how it leads to other things in her life that she regrets, impatience, lack of kindness, judging others, and so she says truthfully, “Yes.”

He recites the words of absolution with an ancient authority that comes to her through his thick Filipino accent, his extremely soft voice. He speaks the words of absolution on behalf of the God she cannot see and cannot believe in as she once had. Standing, his palm raised, through the screen, the ancient words come over her like water, “God the Father of mercies, through the death and resurrection of his Son has reconciled the world to himself and sent the Holy Spirit among us for the forgiveness of sins; through the ministry of the Church may God give you pardon and peace, and I absolve you from your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

“Amen” she says, crossing herself.

“I’m glad you came,” he tells her. “Do you know the Hail Mary?” She answers that she does know it. “Say it once, slowly, and receive your forgiveness. If you commit a mortal sin,” he says and this shocks her, thinking murder, theft, adultery, “come sooner. Otherwise, try to go to mass every Sunday and come back to confession in three months. This is April. So come back in July. Can you do that? Three months, not thirty years,” again, he smiles.

When everyone has come and gone and dusk settles on the roof of the church and the rectory, he emerges through the narrow door, which each person also entered. In the sacristy he removes his vestments, kisses the altar and retires to his small apartment at the rear of the property.

Just inside his front door hangs the first of a series of nautical maps that circle the walls. On the kitchen table, by the toaster, a small collection of maritime paraphernalia that he likes to hold until they warm in his hands, a compact telescope, a brass pulley, a short piece of rope he ties into maritime knots, halyard hitch and cat’s paw, doing it absentmindedly the way another person might handle prayer beads, waiting as the water heats on the stove. On the coffee table, next to his Bible and crucifix, a small scrimshaw carved on whalebone shows the image of a sailor. Made in the nineteenth century, the sailor wears a striped shirt, a necktie, and a neat jacket with buttons. He is surrounded by a wreath of leaves and under the wreath an anchor. Since it was carved before 1973, he reminds himself, whenever his eye falls upon it, that it is legal for him to possess it, which is important as he thinks of himself as a simple, law-abiding priest.

The woman looked up at the high dome before leaving, having said one Hail Mary thoughtfully while kneeling on a pew. She didn’t show the priest her book, hadn’t even thought of it, and put it inside her purse. Come back in three months to see if I’ve improved, she writes on a small paper, like a doctor’s appointment, and then the priest’s final words, which were, “Be happy! It’s Easter!” even though today is Good Friday, which surprised her again. Good Friday, when all the evidence of God’s presence is removed. The day of God’s complete abasement. Not Easter, the day Christ was risen, but the day he was crucified. But this also seems fitting and true. That something good would come from the future, and that it already has, wrapping itself around her, radiating backward three days from Sunday to where she now stands, at the bus stop, squinting into the sun.