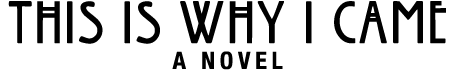

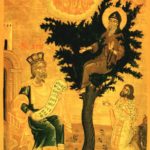

She had come to see if Jesus was remembered, as he had so deeply wanted.

He looked down and saw a woman with cropped brown hair holding small bones, the skull of a snake, a bird wing, leaning on a cane. “Will you tell me about your afternoon with him?” she asked and Zaccheus spoke to her, saying,

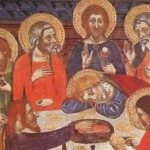

“We ate at my table, oranges, olives.” His voice was slow, infused with a reverie and sadness, as if, for many years, he had wanted to tell this story to someone. “He wasn’t what I expected,” he said then paused. “I could see that he didn’t need me. He didn’t need me to change.

“Sandwiches and fruit,” he continued, each word a break from silence. “He told me, ‘There’s nothing wrong with your body, Zaccheus,’ when I saw my shadow on the dirt. He said, ‘See how whole it is?’ And I thought maybe he was saying, ‘You can stop feeling like a failure now. You can stop feeling like a failure at love.’

“Then night fell and the profile of the hill became clear and harsh and then disappeared. I felt lost again, aswim. My body without circumference, without edge.

“‘Go back to your tree, Zaccheus,’ he said before he left me. ‘It will be paradise for you. Happiness isn’t here, even here with me.’ But his shirt smelled like hammered flax, the honeybee.

“I wanted him to touch me. I wanted him to give me a new way of thinking.

“‘You’ll be safe there,’ he told me at the end of lunch, pointing to these leaves. ‘Things are going to get worse for me.’ That made me angry. This tree, this shadow of the leaf across my foot, my hand on the bark.

“The skin on the backsides of his hands was unusual. And a crack ran through his front tooth. He touched it often with his tongue, telling me a boy hit him in the mouth with a stick. ‘Did I tell you the story of that boy?’ he asked as if we’d been friends a long while. He seemed to have his eye out for that kid, looking away from me several times that afternoon. At the wall, the gate.

“Salt crusts my eyes. I unwrapped his picture and leaned it against this branch. He stood with his foot on the ledge of my pool when I snapped it. He was smiling, can you see? We’d just gotten back. This picture frame casts a sharp shadow so I use it as a clock. His face inside the frame against the branch. I mark my days this way, dividing them into morning and evening, dividing them into hours.

“At night when I fold my sash in front of his picture I think, if I could become a man entirely without purpose I could forget him completely. But even now when I say the word ‘purposeless’ my body springs up to resist it. So you see I have my job cut out.

“Sometimes I say to myself, or to the spider in the cracks of the bark, to the ants, the webbing, I say, ‘It never happened.’ And if I could persuade myself of this, even if only for a few hours, I could begin to say, ‘I have no hunger, I have no thirst.’ But his voice was a low tenor when he sang and he only sang when we walked in my garden. So it’s impossible for me. ‘I feel at home here,’ he said, gesturing to my vines.

“This rust-brown water in my cupped hands. Nothing special.

“When he touched my shoulder something covered me like a film. It was a feeling, a sensation. I think I felt pure-hearted.

“When I scrambled down to show him the way to my house I snagged the toe of my silk slipper. Women laughed at me. The men grabbed the coin purses inside their trousers. I think they worried I’d cheat them again right there, in front of him. At the time, they disgusted me. But now, my toes are covered with black hairs and you can see my feet are like a monkey’s. Now I run along these branches watching for his return. I’ve hung no mirrors. The light turns everything blue. The cart in the far field. The hills that rob the horizon of its purity.

“Mira set out the sweet dates that afternoon, the wine. She hurried to have things ready. I paid her double. We weren’t accustomed to having houseguests. She made me look good. Kind and generous. I tipped her in front of him so he would see my generosity. His hand on my cheek, his voice that found me behind my mask of leaves.

“The commerce of these leaves I break against my skin, the sharp edges cutting in, the pungent smell. I hold them in my palms this way to find him but he isn’t here. Sometimes the fragrance takes me to a palace of memory. The corridors are cool and marble. I climb in to find him. A chair, a throne where he should sit, empty, its eagle’s wings carved and gilded. Once I thought I saw him crouching there behind it, his hands covering his head, the blue band of a silver robe fell around him like a lake. But the image disappeared.

“They ransacked my house. One found the bolt of red silk hidden under my bed, another, my good oil, the dipping spoon, my favorite pillow embroidered with beads. I should have given him the beaded pillow. Feathers flew everywhere. My favorite dresser thrown against this trunk, its delicate inlaid bands of ivory like the fingers of a wife I never had, white and candle-slender, the elongated joints.

“One by one they hurled what they’d taken against the trunk of this tree, yelling epithets. Their anger was like fire. I thought they’d put a torch to this trunk and burn me like a spit goat. But I was lucky. Their voices were truthful. I am not a good man.

“I was angry. I’d already repaid them double but it didn’t matter. My silk pillow filled with lavender. I said, ‘Go ahead! Take it, you lousy bastards!’ The drawers of the dresser fallen out on each other like stairs, the veneer peeled away. The thin bands of ivory, pried out and stolen. The jar broken, the sweet oil dripping down the dresser, precious oil cured by the sun, dried to a black mark. My silk robe, flung open, ripped. My home is occupied by rats now. I see them come and go.

“A man’s voice came up through the branches. It was a Friday. His voice was like a crow caw, jeering. ‘Zaccheus, they killed your hero!’ He threw sand up at me then ran. I wept but I didn’t believe him. That was twenty-seven years ago and thirty-two days. This blue light, his hand on the table, his voice in the wind. I keep a jar of water for him, even though he doesn’t come. Sometimes I call him ‘The visitor who doesn’t come.’

“Every Friday I bind my head with thin branches to honor that rumor, even though I refuse to believe it. I bind my head on Fridays to tell myself the rumor isn’t true. To say the one I love will come back to me. Come back to this tree. I can picture him clearly, walking toward me on stones of forgiveness.

“Today is the Sabbath. My early days here, a young girl came from Jericho with her widowed mother to cultivate balsam, which they sold in the marketplace. Sticky and resinous, used as a medicine and in making perfume. I knew that much. But the young girl said, ‘It mitigates suffering,’ which caught my attention. When she said balsam is also used to embalm the dead, I grew quiet.

“The first time, she tied food in a scarf and raised it into my branches by a rope: palm cake, coconut butter, skewered bits of lamb, a small grilled fish, dried peas. ‘Go away!’ I yelled down at her. ‘Never come back!’ The next time, three dates in a muslin bag. They dangled in the air for weeks. Her kindness was unbearable. I buried the sweet things up high in the trunk.

but she visited me anyway.

“Then she put a flask of water to the end of the rope. I threw it down so it crashed against the ground. Then she went to the river for brackish water. Between the reeds, the green moss floating the way it does, on the surface. ‘It’s unclean,’ she called up to me, so I took it, jerking the jug up quickly and disappearing with it into my leaves.

“The next day I saw her approaching from a distance. She balanced her weight on the dresser drawers, with a hot bowl of lentils and coriander, holding it level as she climbed. ‘Hello,’ she said and I moved downward, toward her. ‘I see you behind those leaves.’ Hunched in the crook of the tree, her bowl of lentils against my bruised and hairy knees. I’d come down from the high branches.

“She gave me lentils in a bowl. Her mother warned her that I was hated and dangerous, but she visited me anyway. ‘He’s an animal, don’t take so much,’ she waved her spoon in the air over the pot. ‘Let him stay in that tree forever, like a prison.’ When she told me this I felt a blankness between them where love could have been. On her sleeve there was a leaf pattern, the beads from my embroidered pillow sewn there. I wondered if she knew where the beads came from.

“Eventually, I moved further out to another sycamore. Past Jericho, past Joshua’s horn. I soaked palm leaves, wove them into mats, offered them to visitors. It was a new generation. People came. I didn’t know what they wanted. It perplexed me at first. They built hermitages. One planted an herb garden with stakes and string. They called their gathering Cellia, the cells. Called themselves monks. One told me they numbered over two hundred, circling my tree. Then there were more. Some stayed a few days, some never left. ‘But what’s here?’ I ask myself. Mats. Leaves. Memories. Emptiness.

“The heart hungers for what is absolute, for a cause worthy of itself, and actual. You know this, Mary of Magdala. Christ on the throne, those Byzantine eyes. I’ve heard how they follow you around a room. That’s what we want, isn’t it? To be seen. That’s what I tell them. My fingers drag a small wake in the dust on this leaf.

“Sometimes I yell at the monks, ‘What was the color of his hair? Tell me the color of his hair! I’m forgetting!’ I scream down at them and they fall silent, pity on their faces. But they didn’t know him. Most of them were too young. Forced to live on stories of him as if it were bread. It’s not the same. This tree emptied of sap, only the fibrous wood of the hours, one after the other and no shape to them. I’m on the lookout just to keep myself from bitterness.

“I have my knife and pen and kite. This small gold bowl. This ring. The water in the marsh will turn blue again. My memory of him, the everlasting sun.

“I think of that young girl and her mother. I don’t know what happened to them. One night in my imagination I traveled to find her, to find what was good between them. I went for the young girl’s sake.”

The rest of the story was told in the Annals of the community, which Mary later read. The record indicated this:

Zaccheus cried for the young girl and her mother. He cried for himself and those he robbed. Most of all he cried for the One who didn’t come back, the One he looked for in the breaking of the leaves. He cried all night. Contrition ran down the bark, stripping away the leaves. Salt joined salt. Sorrow in the gashes.

In the morning, after his night of weeping, a new monk brought Zaccheus food. Expecting to raise it on a rope thrown over the branches, he found the tree bare of leaves.

“Holy Father, Zaccheus!” he called out. When there was no answer, he ventured to the first branch, the second. Found Zaccheus resting high in the crook of the tree. His arms and legs were folded up against his narrow chest, his grey beard stiff, his skin dry, his fingers clamped around a jar of fresh water, a wreath of leaves on his head. Putting his ear to the chest and then the mouth, confirming what he feared, the new monk scrambled down, ran back to his cell, returned with a bolt of red silk, dusty and fraying.

At the same time, the young girl, now married and with children of her own, sat counting the week’s earnings. Her reputation for balsam had grown so that she’d made her husband wealthy and her three sons. Setting coin on top of coin she stopped suddenly, her fingers draping the pile of coins, her mind caught in a day vision of a man crouching behind a throne, wearing a silver robe with blue banding. Leaving the counting table she walked past the river to the sycamore tree where he used to live, seeing, again, the heap of broken things, jagged bits of wood, clay, tattered silks. Her youngest son on her hip, she noted that it was his hunger for righteousness that drew her to him. The hunger to change his life. She had the same hunger. This is a day of turning, she told herself. If I cleave, cleave.

Hearing the news, two thousand monks gathered at the base of the sycamore tree. Carefully they lifted Zaccheus down, wrapped his body in the red cloth. Buried him, with the jug of water, in the new church, beside the high altar.

Among themselves the monks spoke of the purity of his heart. They elected him one of the original twelve, replacing Judas Iscariot. After a period of mourning, they opened the large book and entered the day of his death, listing it as his birth date, to be observed like the feast day of a saint. They spoke of his confidence that the Messiah would return, while noting that he never used the word “Messiah” or any other title, but spoke only of the visitor, using tender nicknames, if he spoke at all.

That night all two thousand monks had the same dream. They learned this the next morning, comparing notes. The details varied somewhat, but each found himself standing in a long marble corridor, a palace of memory, where there was, in the distance, an empty throne. They saw Father Zaccheus crouching behind it in a silver robe, the blue trim of the garment spread around him like a lake.