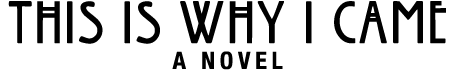

For three days Mary’s mother had refused to bury her husband. She’d resisted all the habits of burial, making enemies of her friends due to what seemed to them a lack of piety. But to her it was piety. “The Lord would never leave me alone with six children!” she’d said, watching the body, sure that God would bring her husband back to life.

Mary had joined her mother, prayed for her father’s return, and when it didn’t happen her mother grew angry. Then she grew sullen and bitter and never again visited the house of the Lord.

On the fourth day she announced, “I keep the Sabbath holy by blaspheming,” brash and unafraid. “I keep the Sabbath holy by taking men into my bed and you will, too.” She fit her daughter with jewelry on her neck and ears, plaiting her hair, and on the fifth day she sent Mary into the streets of Magdala.

“They come here for only one thing,” her mother’s instructions began. “Don’t make friends. Don’t think you are special no matter how often a man returns, no matter how often he says he will leave his wife. They all make promises, they can’t help it. There is only one reason a man comes here and when you give it to him, they leave.” Then she added, “Always take the money first. Count it. And bring it to me.” In this way Mary and her mother fed the boys in the family until they were grown.

Her mother hired other girls. Local ones, foreigners, tall and short, heavy and thin. “For spice,” she said. “Never be boring. Wash yourself. Read. Have things to talk about. Sometimes they just want to talk. But mostly, especially the young ones, they come here for just one thing.”

And so it began. The brothel flourished and Mary forgot about the love she felt as a child for her father. Forgot what it felt like to love and to be loved, to run toward another who waits.

The narrow dirt corridor between the rooms, the hand broom she used to sweep off the sheet, the basin under the bed, the green twigs she lit between customers, bringing them to the doorway, the threshold, to purify it, and then stepping outside onto the doormat, lifting one foot, holding the flame under it, then the other, for cleansing. Checking for sores and bruises.

Mary heard of the raising of Lazarus, heard of threats to the prophet’s life, that he might soon be arrested, and she wanted to meet him while there was still time. “All good men go away,” she told herself but went out in daylight to find him, nonetheless.

Older, being thirty-eight to his thirty-three years, she could see in his eyes that he wanted wisdom in a hurry. She said she had nothing to give, nothing to offer. “But you do,” he protested.

She felt most comfortable with men sure to leave. Married men. Soldiers. Even, once, an old man near death. She had, since thirteen, learned to not mourn, to brush her hair afterward, to clean her teeth. “I know how to get past love. I’m older than you are. I’ve had many.” But Jesus argued with her, saying, “That’s not true.”

“You’ll just get hurt,” her mother warned, seeing that she was nervous each time they met. She knew he didn’t want what other men sought in her yet she found herself fearing he wouldn’t return because, with him, she remembered her father and felt again that wound.

It was her childlike quality Jesus found attractive. That she was tough but also fragile. They made a game of it, Jesus hiding his face behind his hands then popping out, saying, “Hah!” which startled her every single time because, somehow, she thought once gone, gone forever. It startled her even when he did it five times in a row. “I’m coming back,” he told her each time they parted. “You’ll see.”

“On the third day I’m going to rise from the dead,” he said near the end, which angered her because it was specific and he seemed so convinced of it.

“Of course you are,” she humored him. She’d encountered men with wild visions before. One would be an emperor, another, a general. This was part of her job, to hold these daydreams as if they could happen. It was a form of play, almost sexual, like costumes and masks, whips and ankle cuffs. She obliged men this way as a courtesy, to keep them coming back, and had long ago mastered the expression of seriousness.

But Jesus was not a customer. They were friends. And she loved him. “Don’t say that,” she rebuked him. She wanted his leaving, if he must leave, to take a simpler form. Without the fantasies, the outlandishness. “I like everything about you but your false promises,” she chided. But then she grew anxious and softened, that this might really be true, and said, “If it’s going to happen as you say, give your mother to John. He will be good to her.”

Jesus took her to the river where he and his mother had buried the myrrh. When they walked through the streets men whistled, women turned away and looked down hissing until she passed. He was talking about his death all the time then. Since Lazarus.

They dug in the mud for the jar. On her knees, her dress dampened, dirt in her fingernails.

“Use it on me,” he said, “when the time comes. Remember me,” he said.

“You’re always asking me to do that.”

“When you eat bread think of me. Think of me when you drink from a cup. I mean this,” he pleaded.

“I will remember you, my prince, for the rest of my life.”

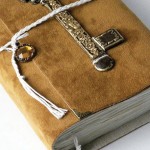

Tilman Riemenschneider

Mary in Mourning, circa 1505

Mary in Mourning (c. 1505) by Christ Bearers is in the public domain.