From Mary:

On a flight I sat behind three young women, perhaps in their twenties, who discussed what they were reading, clicking on their devices as they spoke, referencing online bloggers, reviews. None spoke of The New York Times or The New York Review of Books and I thought, there is a divide here and it’s generational.

I started to wonder if anyone under age 50 would ever hear of my novel much less read it.

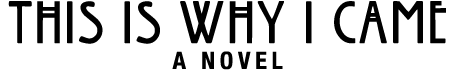

During a photo session for the novel’s website I met Marielle. She told me she was 22. I wondered if she’d be willing to read a chapter of This is Why I Came and respond in a Guest Blog. She graciously said yes. It didn’t at all matter to me if she hated or loved the chapter, or if she put it down after reading one sentence and wrote her blog about that. This is not because I am a generous person. It has to do with how art is made. It has to do with what art is.

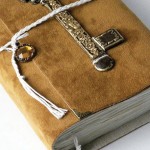

The astonishing sculptor David Nash explains, referencing Duchamp, that work is completed in the act of being seen. The artist only does half of the job. The other half is provided by the perceiver. The same is true of writing. Of music.

This is not fancy art-theory. This is something felt in the body even before one learns about art or about criticism. The body knows this primary fact already because the body is built to make and to receive art. Art is not superfluous to the body, to sight, to hearing, to touch. It is the opposite. To the body, art is food. It is water. It is air.

Marielle’s response was a happy surprise for me. Her Christian upbringing, her personal take on the chapter, her choice of chapter. And all of these are good. But they are a bonus. It is never necessary to be liked or for the work to be admired. The work needs only to be finally, completely made. That is what the work itself longs for. That the half circle which the writer makes, the sculptor or composer makes, be made whole.

For another treat, enjoy this gorgeous interview with David Nash (see at 5 min).

Who comes to mind when you think about significant women in history?

Most people would offer names such as Cleopatra, Joan of Arc, Eleanor Roosevelt or Oprah Winfrey. These are all such purposeful women that have contributed to history in some way and have earned their place in our memory for one reason or another.

But the ones we often forget are all saved away in one book: the Bible. We just never seem to think of the women in here because the men of the Bible often steal the show.

I’ve attended a Christian school for 17 years. I went to a small, private Christian school from preschool to senior graduation. Then I attended and graduated from a private Christian college. I’ve learned the Bible stories backwards and forwards. In fact, these timeless stories were engraved in my mind even before I realized it.

And yet, when I think about the Bible, I often forget it houses many of the most heroic women in history.

I recently saw a tweet that said, “The Bible is a very bloke-y kind of book. Women don’t get a lot of ink,” from Leonard Lopate of The Leonard Lopate Show. This seems like a pretty common thought.

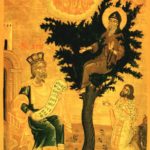

The women of the Bible that we do think about are often a slim few. Most likely an image of the nativity scene appears in your head with Jesus’ mother, Mary, tucked away in a manger surrounded by wise men and farm animals.

Or perhaps you think of Adam’s counterpart Eve, holding out the forbidden fruit that changed humanity’s relationship with God forever. Even the beautiful Bathsheba, bathing on a rooftop under the lustful gaze of King David, may come to mind.

Besides Mary or Eve, rarely do the women of the Bible make their mark in the minds of the readers. And what a shame seeing as there are inspiring stories of strength scattered throughout the Bible’s pages.

Mary, mother of Jesus, no doubt endured 9 months of ridicule and questioning from her community (and even her own husband) as her belly grew despite being unmarried.

Jael, the wife of Heber, killed the leader of the enemy army, Sisera, with a plunge of a tent peg to his temple while he slept in her tent.

Deborah stepped up to lead a nation when all the men around her ran scared.

Rahab the harlot risked her life by lying to her country’s soldiers looking for spies from Joshua’s camp in order to save their lives and help them flee the country.

Esther. Ruth. Mary Magdalene. Abigail. The list goes on.

But I never thought deeply about Rebekah. Isaac was simply the son of Abraham, father of Jacob, and Rebekah was his wife.

But there is a beautiful connection in this chapter that represents a much bigger theme for me.

Isaac realizes that he loves Rebekah not because of her beauty or skills, or some of the things we normally associate with reasons to love someone; he loves her because she is strong and purposeful. She is his companion and confidante.

He sees this when she reassures him of who he is. He sees this as she bears his children. He even sees this when she makes decisions that wrong him and his eldest son. Her resolve is important to him.

This relationship between Isaac and Rebekah — his respect for the woman he loves, despite her wrongdoings— illuminates such a beautiful topic: admiration for the strength and purpose of a woman with a vision.

Marielle Sedin

Marielle Sedin is Junior Content Specialist with LaunchPodium in San Francisco. She can be contacted at [email protected]