From Mary:

I go to art, poetry, stand-up comedy to encounter a unique take on the world, one that is not my own. I suspect that this is the source of genius in every field, whether mathematics, architecture, fashion. That a person has a unique perception and is making it manifest.

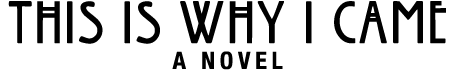

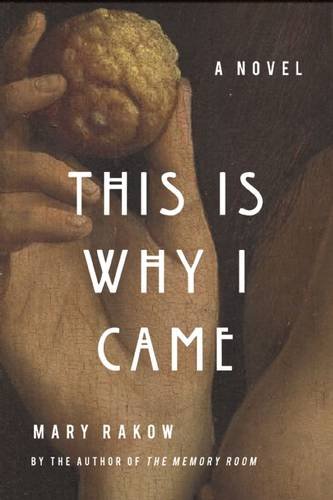

I invited Rochelle Low to comment on one of the chapters in This is Why I Came because her manner of associating one thing with another is what I like about her thinking. Always sort of out of left field to me at first, and then, a bit later, totally right.

When I was a child, God was lovely. An immense billowy white beard, hair down his back, in a white Grecian gown, descending a stairway from Heaven. When I imagined him speaking, his voice was cavernous, yet kind. I was not afraid of him as I was of my Grandfather, Samuel, nervous and rail thin, his hands trembling as he ate his soft-boiled egg from his personally engraved porcelain cup each morning. “Papa is not well,” my mother would whisper to me. He suffered a stroke upon arriving in America from Germany at the age of forty-nine, and never worked again.

When I was five, I went to Saturday School where I first learned the story of Noah, and I’m sure I loved Noah as I loved God then, because I saw God’s will as benevolent. And when I went to Synagogue with my Grandmother Celia, both of us sitting in the balcony, observing the men below taking the sacred Torah from it’s cabinet encased in the deepest of colors of velvets and satins, lovingly fingering its holiness. “This is where the stories come from, Mamela,” she would tell me. What she never told me was that her brother, Beryl, a rabbi in Cracow, had been murdered with his wife in 1940 by the Nazis. So my God remained benevolent.

As a young adult, I was passionate and marched against a war in Asia that caused immeasurable suffering. The God of my childhood slowly disappeared and as my grandparents and parents passed away out of this life, the rituals that I was indoctrinated with, also disappeared.

Having just returned with my family from Eastern Europe which included a trip to Auschwitz, I read This is Why I Came, and the God that I had come to believe in as an adult appeared. The story of Noah, a man blithely marching his family and animals up a plank in order to save mankind, became a nightmare. It is clear that he obeyed a violent and petulant God, a petty and narcissistic Deity, who was not only capable of nurturing genocide, but whose resentments justified him doing so.

Two by two they were brought to safety the Bible tells us. But what of the Jews who were brought in railroad cars by the hundreds, without water or sustenance. Where was Noah? Was he sulking? Was it too much for him, the thought of taking them in again? Couldn’t God have had him put out the fires that incinerated them?

His chosen people have become relics, salesmen of extravagant ancient houses of worship to sustain their communities. I bought the last ticket to a concert in the Spanish Synagogue in Prague the following Sunday. “Tonight,” the woman in the booth told me, “is Shabus,” the Yiddish word for sabbath. They were closing early. They remain obedient, observant. Again, like the battered woman who has just received a diamond bracelet from the man who bloodied her eyes yesterday, God and Noah are good.

Rochelle Low

Rochelle Low is a poet and novelist living in Los Angeles. A secular Jew, she is interested in spiritual and religious matters and is most drawn to Buddhism. She can be contacted at: [email protected].